Dance

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (June 2023) |

| Part of a series on |

| Performing arts |

|---|

Dance is an art form, consisting of sequences of body movements with aesthetic and often symbolic value, either improvised or purposefully selected. Dance can be categorized and described by its choreography, by its repertoire of movements or by its historical period or place of origin. Dance is typically performed with musical accompaniment, and sometimes with the dancer simultaneously using a musical instrument themselves.

There are two different types of dance: theatrical and participatory dance. Both types of dance may have special functions, whether social, ceremonial, competitive, erotic, martial, sacred or liturgical. Dance is not solely restricted to performance, as dance is used as a form of exercise and occasionally training for other sports and activities. Dance performances and dancing competitions are found across the world exhibiting various different styles and standards.

Theatrical and participatory dance

Theatrical dance, also called performance or concert dance, is intended primarily as a spectacle, usually a performance upon a stage by virtuoso dancers. It often tells a story, perhaps using mime, costume and scenery, or it may interpret the musical accompaniment, which is often specially composed and performed in a theatre setting but it is not a requirement. Examples are Western ballet and modern dance, Classical Indian dance such as Bharatanatyam, and Chinese and Japanese song and dance dramas, such as the dragon dance. Most classical forms are centred upon dance alone, but performance dance may also appear in opera and other forms of musical theatre.

Participatory dance, whether it be a folk dance, a social dance, a group dance such as a line, circle, chain or square dance, or a partner dance, such as in Western ballroom dancing, is undertaken primarily for a common purpose, such as social interaction or exercise, or building flexibility of participants rather than to serve any benefit to onlookers. Such dance seldom has any narrative. A group dance and a corps de ballet, a social partner dance and a pas de deux, differ profoundly. Even a solo dance or interpretive dance may be undertaken solely for the satisfaction of the dancer. Participatory dancers often all employ the same movements and steps but, for example, in the rave culture of electronic dance music, vast crowds may engage in free dance, uncoordinated with those around them. On the other hand, some cultures lay down strict rules as to the particular dances people may or must participate.[1]

History

Archaeological evidence for early dance includes 10,000-years-old paintings in Madhya Pradesh, India at the Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka,[2] and Egyptian tomb paintings depicting dancing figures, dated c. 3300 BC. It has been proposed that before the invention of written languages, dance was an important part of the oral and performance methods of passing stories down from one generation to the next.[3] The use of dance in ecstatic trance states and healing rituals (as observed today in many contemporary indigenous cultures) is thought to have been another early factor in the social development of dance.[4]

References to dance can be found in very early recorded history; Greek dance (choros) is referred to by Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch and Lucian.[5] The Bible and Talmud refer to many events related to dance, and contain over 30 different dance terms.[6] In Chinese pottery as early as the Neolithic period, groups of people are depicted dancing in a line holding hands,[7] and the earliest Chinese word for "dance" is found written in the oracle bones.[8] Dance is described in the Lüshi Chunqiu.[9][10] Primitive dance in ancient China was associated with sorcery and shamanic rituals.[11]

During the first millennium BCE in India, many texts were composed which attempted to codify aspects of daily life. Bharata Muni's Natya Shastra (literally "the text of dramaturgy") is one early text. It mainly deals with drama, in which dance plays an important part in Indian culture. A strong continuous tradition of dance has since continued in India, through to modern times, where it continues to play a role in culture, ritual, and the Bollywood entertainment industry. Many other contemporary dance forms can likewise be traced back to historical, traditional, ceremonial, and ethnic dance.[12]

Music

Dance is generally, but not exclusively, performed with the accompaniment of music and may or may not be performed in time to such music. Some dance (such as tap dance or gumboot dance) may provide its own audible accompaniment in place of (or in addition to) music. Many early forms of music and dance were created for each other and are frequently performed together. Notable examples of traditional dance-music couplings include the jig, waltz, tango, disco, and salsa. Some musical genres have a parallel dance form such as baroque music and baroque dance; other varieties of dance and music may share nomenclature but developed separately, such as classical music and classical ballet. The choreography and music are meant to complement each other, to express a story told by the choreographer and dancers.[13]

Rhythm

Rhythm and dance are deeply linked in history and practice. The American dancer Ted Shawn wrote; "The conception of rhythm which underlies all studies of the dance is something about which we could talk forever, and still not finish."[14] A musical rhythm requires two main elements; a regularly-repeating pulse (also called the "beat" or "tactus") that establishes the tempo, and a pattern of accents and rests that establishes the character of the metre or basic rhythmic pattern. The basic pulse is roughly equal in duration to a simple step or gesture.

Dances generally have a characteristic tempo and rhythmic pattern. The tango, for example, is usually danced in 2

4 time at approximately 66 beats per minute. The basic slow step, called a "slow", lasts for one beat, so that a full "right–left" step is equal to one 2

4 measure. The basic forward and backward walk of the dance is so counted – "slow-slow" – while many additional figures are counted "slow – quick-quick".[15]

Repetitive body movements often depend on alternating "strong" and "weak" muscular movements.[16] Given this alternation of left-right, of forward-backward and rise-fall, along with the bilateral symmetry of the human body, many dances and much music are in duple and quadruple meter. Since some such movements require more time in one phase than the other – such as the longer time required to lift a hammer than to strike – some dance rhythms fall into triple metre.[17] Occasionally, as in the folk dances of the Balkans, dance traditions depend heavily on more complex rhythms. Complex dances composed of a fixed sequence of steps require phrases and melodies of a certain fixed length to accompany that sequence.

Musical accompaniment arose in the earliest dance, so that ancient Egyptians attributed the origin of the dance to the divine Athotus, who was said to have observed that music accompanying religious rituals caused participants to move rhythmically and to have brought these movements into proportional measure. The idea that dance arises from musical rhythm, was found in renaissance Europe, in the works of the dancer Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro. Pesaro speaks of dance as a physical movement that arises from and expresses inward, spiritual motion agreeing with the "measures and perfect concords of harmony" that fall upon the human ear,[16] while earlier, Mechthild of Magdeburg, seizing upon dance as a symbol of the holy life foreshadowed in Jesus' saying "I have piped and ye have not danced",[18] writes;

I can not dance unless thou leadest. If thou wouldst have me spring aloft, sing thou and I will spring, into love and from love to knowledge and from knowledge to ecstasy above all human sense[19]

Thoinot Arbeau's celebrated 16th-century dance-treatise Orchésographie, indeed, begins with definitions of over eighty distinct drum-rhythms.[20]

Dance has been represented through the ages as having emerged as a response to music yet, as Lincoln Kirstein implied, it is at least as likely that primitive music arose from dance. Shawn concurs, stating that dance "was the first art of the human race, and the matrix out of which all other arts grew" and that even the "metre in our poetry today is a result of the accents necessitated by body movement, as the dancing and reciting was performed simultaneously"[14] – an assertion somewhat supported by the common use of the term "foot" to describe the fundamental rhythmic units of poetry.

Scholes, a musician, offers support for this view, stating that the steady measures of music, of two, three or four beats to the bar, its equal and balanced phrases, regular cadences, contrasts and repetitions, may all be attributed to the "incalculable" influence of dance upon music.[21]

Hence, Shawn asserts, "it is quite possible to develop the dance without music and... music is perfectly capable of standing on its own feet without any assistance from the dance", nevertheless the "two arts will always be related and the relationship can be profitable both to the dance and to music",[22] the precedence of one art over the other being a moot point. The common ballad measures of hymns and folk-songs takes their name from dance, as does the carol, originally a circle dance. Many purely musical pieces have been named "waltz" or "minuet", for example, while many concert dances have been produced that are based upon abstract musical pieces, such as 2 and 3 Part Inventions, Adams Violin Concerto and Andantino. Similarly, poems are often structured and named after dances or musical works, while dance and music have both drawn their conception of "measure" or "metre" from poetry.

Shawn quotes with approval the statement of Dalcroze that, while the art of musical rhythm consists in differentiating and combining time durations, pauses and accents "according to physiological law", that of "plastic rhythm" (i.e. dance) "is to designate movement in space, to interpret long time-values by slow movements and short ones by quick movements, regulate pauses by their divers successions and express sound accentuations in their multiple nuances by additions of bodily weight, by means of muscular innervations".

Shawn points out that the system of musical time is a "man-made, artificial thing.... a manufactured tool, whereas rhythm is something that has always existed and depends on man not at all", being "the continuous flowing time which our human minds cut up into convenient units", suggesting that music might be revivified by a return to the values and the time-perception of dancing.[23]

The early-20th-century American dancer Helen Moller stated that "it is rhythm and form more than harmony and color which, from the beginning, has bound music, poetry and dancing together in a union that is indissoluble."[24][nb 1]

Approaches

Theatrical

Concert dance, like opera, generally depends for its large-scale form upon a narrative dramatic structure. The movements and gestures of the choreography are primarily intended to mime the personality and aims of the characters and their part in the plot.[29] Such theatrical requirements tend towards longer, freer movements than those usual in non-narrative dance styles. On the other hand, the ballet blanc, developed in the 19th century, allows interludes of rhythmic dance that developed into entirely "plotless" ballets in the 20th century[30] and that allowed fast, rhythmic dance-steps such as those of the petit allegro. A well-known example is The Cygnets' Dance in act two of Swan Lake.

The ballet developed out of courtly dramatic productions of 16th- and 17th-century France and Italy and for some time dancers performed dances developed from those familiar from the musical suite,[31] all of which were defined by definite rhythms closely identified with each dance. These appeared as character dances in the era of romantic nationalism.

Ballet reached widespread vogue in the romantic era, accompanied by a larger orchestra and grander musical conceptions that did not lend themselves easily to rhythmic clarity and by dance that emphasised dramatic mime. A broader concept of rhythm was needed, that which Rudolf Laban terms the "rhythm and shape" of movement that communicates character, emotion and intention,[32] while only certain scenes required the exact synchronisation of step and music essential to other dance styles, so that, to Laban, modern Europeans seemed totally unable to grasp the meaning of "primitive rhythmic movements",[33] a situation that began to change in the 20th century with such productions as Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring with its new rhythmic language evoking primal feelings of a primitive past.[34]

Indian classical dance styles, like ballet, are often in dramatic form, so that there is a similar complementarity between narrative expression and "pure" dance. In this case, the two are separately defined, though not always separately performed. The rhythmic elements, which are abstract and technical, are known as nritta. Both this and expressive dance (nritya), though, are closely tied to the rhythmic system (tala). Teachers have adapted the spoken rhythmic mnemonic system called bol to the needs of dancers.

Japanese classical dance-theatre styles such as Kabuki and Noh, like Indian dance-drama, distinguish between narrative and abstract dance productions. The three main categories of kabuki are jidaimono (historical), sewamono (domestic) and shosagoto (dance pieces).[35] Somewhat similarly, Noh distinguishes between Geki Noh, based around the advancement of plot and the narration of action, and Furyū Noh, dance pieces involving acrobatics, stage properties, multiple characters and elaborate stage action.[36]

Participatory and Social

Social dances, those intended for participation rather than for an audience, may include various forms of mime and narrative, but are typically set much more closely to the rhythmic pattern of music, so that terms like waltz and polka refer as much to musical pieces as to the dance itself. The rhythm of the dancers' feet may even form an essential part of the music, as in tap dance. African dance, for example, is rooted in fixed basic steps, but may also allow a high degree of rhythmic interpretation: the feet or the trunk mark the basic pulse while cross-rhythms are picked up by shoulders, knees, or head, with the best dancers simultaneously giving plastic expression to all the elements of the polyrhythmic pattern.[37]

Cultural traditions

Africa

Dance in Africa is deeply integrated into society and major events in a community are frequently reflected in dances: dances are performed for births and funerals, weddings and wars.[38]: 13 Traditional dances impart cultural morals, including religious traditions and sexual standards; give vent to repressed emotions, such as grief; motivate community members to cooperate, whether fighting wars or grinding grain; enact spiritual rituals; and contribute to social cohesiveness.[39]

Thousands of dances are performed around the continent. These may be divided into traditional, neotraditional, and classical styles: folkloric dances of a particular society, dances created more recently in imitation of traditional styles, and dances transmitted more formally in schools or private lessons.[38]: 18 African dance has been altered by many forces, such as European missionaries and colonialist governments, who often suppressed local dance traditions as licentious or distracting.[39] Dance in contemporary African cultures still serves its traditional functions in new contexts; dance may celebrate the inauguration of a hospital, build community for rural migrants in unfamiliar cities, and be incorporated into Christian church ceremonies.[39][40]

Asia

All Indian classical dances are to varying degrees rooted in the Natyashastra and therefore share common features: for example, the mudras (hand positions), some body positions, leg movement and the inclusion of dramatic or expressive acting or abhinaya. Indian classical music provides accompaniment and dancers of nearly all the styles wear bells around their ankles to counterpoint and complement the percussion.

There are now many regional varieties of Indian classical dance. Dances like "Odra Magadhi", which after decades-long debate, has been traced to present day Mithila, Odisha region's dance form of Odissi (Orissi), indicate influence of dances in cultural interactions between different regions.[41]

The Punjab area overlapping India and Pakistan is the place of origin of Bhangra. It is widely known both as a style of music and a dance. It is mostly related to ancient harvest celebrations, love, patriotism or social issues. Its music is coordinated by a musical instrument called the 'Dhol'. Bhangra is not just music but a dance, a celebration of the harvest where people beat the dhol (drum), sing Boliyaan (lyrics) and dance. It developed further with the Vaisakhi festival of the Sikhs.

The dances of Sri Lanka include the devil dances (yakun natima), a carefully crafted ritual reaching far back into Sri Lanka's pre-Buddhist past that combines ancient "Ayurvedic" concepts of disease causation with psychological manipulation and combines many aspects including Sinhalese cosmology. Their influence can be seen on the classical dances of Sri Lanka.[42]

Indonesian dances reflect the richness and diversity of Indonesian ethnic groups and cultures. There are more than 1,300 ethnic groups in Indonesia, it can be seen from the cultural roots of the Austronesian and Melanesian peoples, and various cultural influences from Asia and the west. Dances in Indonesia originate from ritual movements and religious ceremonies, this kind of dance usually begins with rituals, such as war dances, shaman dances to cure or ward off disease, dances to call rain and other types of dances. With the acceptance of dharma religion in the 1st century in Indonesia, Hinduism and Buddhist rituals were celebrated in various artistic performances. Hindu epics such as the Ramayana, Mahabharata and also the Panji became the inspiration to be shown in a dance-drama called "Sendratari" resembling "ballet" in the western tradition. An elaborate and highly stylized dance method was invented and has survived to this day, especially on the islands of Java and Bali. The Javanese Wayang wong dance takes footage from the Ramayana or Mahabharata episodes, but this dance is very different from the Indian version, indonesian dances do not pay as much attention to the "mudras" as Indian dances: even more to show local forms. The sacred Javanese ritual dance Bedhaya is believed to date back to the Majapahit period in the 14th century or even earlier, this dance originated from ritual dances performed by virgin girls to worship Hindu Gods such as Shiva, Brahma, and Vishnu. In Bali, dance has become an integral part of the sacred Hindu Dharma rituals. Some experts believe that Balinese dance comes from an older dance tradition from Java. Reliefs from temples in East Java from the 14th century feature crowns and headdresses similar to the headdresses used in Balinese dance today. Islam began to spread to the Indonesian archipelago when indigenous dances and dharma dances were still popular. Artists and dancers still use styles from the previous era, replacing stories with more Islamic interpretations and clothing that is more closed according to Islamic teachings.[43]

The dances of the Middle East are usually the traditional forms of circle dancing which are modernized to an extent. They would include dabke, tamzara, Assyrian folk dance, Kurdish dance, Armenian dance and Turkish dance, among others.[44][45] All these forms of dances would usually involve participants engaging each other by holding hands or arms (depending on the style of the dance). They would make rhythmic moves with their legs and shoulders as they curve around the dance floor. The head of the dance would generally hold a cane or handkerchief.[44][46]

Europe and North America

Folk dances vary across Europe and may date back hundreds or thousands of years, but many have features in common such as group participation led by a caller, hand-holding or arm-linking between participants, and fixed musical forms known as caroles.[47] Some, such as the maypole dance are common to many nations, while others such as the céilidh and the polka are deeply-rooted in a single culture. Some European folk dances such as the square dance were brought to the New World and subsequently became part of American culture.

Ballet developed first in Italy and then in France from lavish court spectacles that combined rhythm, drama, poetry, song, costumes and dance. Members of the court nobility took part as performers. During the reign of Louis XIV, himself a dancer, dance became more codified. Professional dancers began to take the place of court amateurs, and ballet masters were licensed by the French government. The first ballet dance academy was the Académie Royale de Danse (Royal Dance Academy), opened in Paris in 1661. Shortly thereafter, the first institutionalized ballet troupe, associated with the academy, was formed; this troupe began as an all-male ensemble but by 1681 opened to include women as well.[3]

20th century concert dance brought an explosion of innovation in dance style characterized by an exploration of freer technique. Early pioneers of what became known as modern dance include Loie Fuller, Isadora Duncan, Mary Wigman and Ruth St. Denis. The relationship of music to dance serves as the basis for Eurhythmics, devised by Emile Jaques-Dalcroze, which was influential to the development of Modern dance and modern ballet through artists such as Marie Rambert. Eurythmy, developed by Rudolf Steiner and Marie Steiner-von Sivers, combines formal elements reminiscent of traditional dance with the new freer style, and introduced a complex new vocabulary to dance. In the 1920s, important founders of the new style such as Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey began their work. Since this time, a wide variety of dance styles have been developed; see Modern dance.

African American dance developed in everyday spaces, rather than in dance studios, schools or companies. Tap dance, disco, jazz dance, swing dance, hip hop dance, the lindy hop with its relationship to rock and roll music and rock and roll dance have had a global influence. Dance styles fusing classical ballet technique with African-American dance have also appeared in the 21st century, including Hiplet.[48]

Latin America

Dance is central to Latin American social life and culture. Brazilian Samba, Argentinian tango, and Cuban salsa are internationally popular partner dances, and other national dances—merengue, cueca, plena, jarabe, joropo, marinera, cumbia, bachata and others—are important components of their respective countries' cultures.[49] Traditional Carnival festivals incorporate these and other dances in enormous celebrations.[50]

Dance has played an important role in forging a collective identity among the many cultural and ethnic groups of Latin America.[51] Dance served to unite the many African, European, and indigenous peoples of the region.[49] Certain dance genres, such as capoeira, and body movements, especially the characteristic quebradas or pelvis swings, have been variously banned and celebrated throughout Latin American history.[51]

Education

Dance studies are offered through the arts and humanities programs of many higher education institutions. Some universities offer Bachelor of Arts and higher academic degrees in Dance. A dance study curriculum may encompass a diverse range of courses and topics, including dance practice and performance, choreography, ethnochoreology, kinesiology, dance notation, and dance therapy. Most recently, dance and movement therapy has been integrated in some schools into math lessons for students with learning disabilities, emotional or behavioral disabilities, as well as for those with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[52]

Dance is taught to all ages ranging from two years old to the adult level outside of a professional dance setting. Typically this dance education is seen in dance studio businesses across the world.[53] Some K-12 public schools have provided the opportunity for students to take beginner level dance classes, as well as participate in dance teams that perform at school events. [54]

Occupations

Dancers

Professional dancers are usually employed on contract or for particular performances or productions. The professional life of a dancer is generally one of constantly changing work situations, strong competitive pressure and low pay. Consequently, professional dancers often must supplement their incomes to achieve financial stability. In the U.S. many professional dancers belong to unions (such as the American Guild of Musical Artists, Screen Actors Guild and Actors' Equity Association) that establish working conditions and minimum salaries for their members. Professional dancers must possess large amounts of athleticism. To lead a successful career, it is advantageous to be versatile in many styles of dance, have a strong technical background and to use other forms of physical training to remain fit and healthy.[55]

Teachers

Dance teachers typically focus on teaching dance performance, or coaching competitive dancers, or both. They typically have performance experience in the types of dance they teach or coach. For example, dancesport teachers and coaches are often tournament dancers or former dancesport performers. Dance teachers may be self-employed, or employed by dance schools or general education institutions with dance programs. Some work for university programs or other schools that are associated with professional classical dance (e.g., ballet) or modern dance companies. Others are employed by smaller, privately owned dance schools that offer dance training and performance coaching for various types of dance.[56]

Choreographers

Choreographers are the ones that design the dancing movements within a dance, they are often university trained and are typically employed for particular projects or, more rarely may work on contract as the resident choreographer for a specific dance company.[57][58]

Competitions

A dance competition is an organized event in which contestants perform dances before a judge or judges for awards, and in some cases, monetary prizes. There are several major types of dance competitions, distinguished primarily by the style or styles of dances performed. Dance competitions are an excellent setting to build connections with industry leading faculty members, adjudicators, choreographers and other dancers from competing studios. A typical dance competition for younger pre-professional dancers can last anywhere between two and four days, depending whether it is a regional or national competition.

The purpose of dance competitions is to provide a fun and educative place for dancers and give them the opportunity to perform their choreographed routines from their current dance season onstage. Oftentimes, competitions will take place in a professional setting or may vary to non-performance spaces, such as a high school theatre. The results of the dancers are then dictated by a credible panel of judges and are evaluated on their performance than given a score. As far as competitive categories go, most competitions base their categories according to the dance style, age, experience level and the number of dancers competing in the routine.[59] Major types of dance competitions include:

- Dancesport, which is focused exclusively on ballroom and latin dance.

- Competitive dance, in which a variety of theater dance styles, such as acrobatics, ballet, jazz, hip-hop, lyrical, stepping, and tap, are permitted.

- Commercial Dance, consisting of as hip hop, jazz, locking, popping, breakdancing, contemporary etc.[59]

- Single-style competitions, such as; highland dance, dance team, and Irish dance, that only permit a single dance style.

- Open competitions, that permit a wide variety of dance styles. An example of this is the TV program So You Think You Can Dance.

- Olympic, Dance has been trying to be part of the Olympic sport since 1930s.

Dance diplomacy

During the 1950s and 1960s, cultural exchange of dance was a common feature of international diplomacy, especially amongst East and South Asian nations. The People's Republic of China, for example, developed a formula for dance diplomacy that sought to learn from and express respect for the aesthetic traditions of recently independent states that were former European colonies, such as Indonesia, India, and Burma, as a show of anti-colonial solidarity.[60]

Health

Footwear

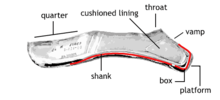

In most forms of dance the foot is the source of movement, and in some cases require specific shoes to aid in the health, safety ability of the dancer, depending on the type of dance, the intensity of the movements, and the surface that will be danced on.

Dance footwear can be potentially both supportive and or restrictive to the movement of the dancer.[61] The effectiveness of the shoe is related to its ability to help the foot do something it is not intended to do, or to make easier a difficult movement. Such effects relate to health and safety because of the function of the equipment as unnatural to the bodies usual mobility.

Ballet

Ballet is notable for the risks of injury due to the biomechanics of the ankle and the toes as the main support for the rest of the movements. With the pointe shoe, the design specifically brings all of the toes together to allow the toes to be stood on for longer periods of time.[62]

There are accessories associated with pointe shoes that help to mitigate injury and soothe pain while dancing, including things such as toe pads, toe tape, and cushions.[63]

Body image

Dancers are publicly thought to be very preoccupied with their body image to fit a certain mold in the industry. Research indicates that dancers do have greater difficulty controlling their eating habits as a large quantity strive for the art-form's ideal body mass. Some dancers often resort to abusive tactics to maintain a certain image. Common scenarios include dancers abusing laxatives for weight control and end up falling into unhealthy eating disorders. Studies show that a large quantity of dancers use at least one method of weight control including over exercising and food restriction. The pressure for dancers to maintain a below average weight affects their eating and weight controlling behaviours and their life-style.[64] Due to its artistic nature, dancers tend to have many hostile self-critical tendencies. Commonly seen in performers, it is likely that a variety of individuals may be resistant to concepts of self-compassion.[65]

Eating disorders

In North America, eating disorders present a significant public health challenge, with an estimated 10% of young girls affected. Those engaged in aesthetic-focused sports like dance face even greater risks due to intense pressures for a slender physique.[66] Eating disorders in dancers are generally very common. Through data analysis and studies published, sufficient data regarding the percentage and accuracy dancers have of realistically falling into unhealthy disordered eating habits or the development of an eating disorder were extracted. Dancers, in general, have a higher risk of developing eating disorders than the general public, primarily falling into anorexia nervosa and EDNOS. Research has yet to distinguish a direct correlation regarding dancers having a higher risk of developing bulimia nervosa. Studies concluded that dancers overall have a three times higher risk of developing eating disorders, more specifically anorexia nervosa and EDNOS.[67]

Dance on social media

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (June 2023) |

Dance has become a popular form of content across many social media platforms, including TikTok. During 2020, TikTok dances offered the opportunity for isolated individuals to interact and connect with one another through a virtual format.[68] Since its debut in 2017, the app has also attracted a small but growing audience of professional dancers in their early 20s to 30s. While the majority of this demographic is more accustomed to performing onstage, this app introduced a new means to generate professional exposure.[69]

Gallery

-

A satyr dancing. A fresco from the cubiculum in the Villa of the Mysteries. From Pompeii. Date: 80 to 70 BCE [70]

-

Folk dance – a trio of Irish Stepdancers performing in competition

-

A contemporary dancer performs a stag split leap.

-

Dance partnering – a male dancer assists a female dancer in performing an arabesque, as part of a classical pas de deux.

-

Acrobatic dance – an acro dancer performs a front aerial.

-

A dancer performs a "toe rise", in which she rises from a kneeling position to a standing position on the tops of her feet.

-

Social dance – dancers at a juke joint dance the Jitterbug, an early 20th century dance that would go on to influence swing, jive, and jazz dance.

-

Latin Ballroom dancers perform the Tango.

-

Gumboot dance evolved from the stomping signals used as coded communication between labourers in South African mines.

-

-

A hip-hop dancer demonstrates popping.

-

Erotic dance – a pole dancer performs a routine.

-

Prop dance – a fire dancer performance

-

Modern dance – a dancer performs a leg split while balanced on the back of her partner.

-

Stage dance – a professional dancer at the Bolshoi Theatre

-

A nineteenth century artist's representation of a Flamenco dancer

-

Ritual dance – Armenian folk dancers celebrate a neo-pagan new year.

-

A latin ballroom couple perform a Samba routine at a dancesport event.

-

Folk dance – some dance traditions travel with immigrant communities, as with this festival dance performed by a Polish community in Turkey.

-

A ballet dancer performs a standing side split.

-

Street dance – a Breakdancer performs a handstand trick.

-

Ballet class of young girls wearing leotards and skirts in 2017

-

Kebagh dance from Pagar Alam, Indonesia

-

Balinese dance

See also

- Art

- Outline of performing arts

- Outline of dance

- List of dancers

- List of dances

- List of dance awards

- Index of dance articles

Notes

References

- ^ "Theatrical and Social Dance | sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk". sound-heritage.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2024-12-07. Retrieved 2024-10-22.

- ^ Mathpal, Yashodhar (1984). Prehistoric Painting Of Bhimbetka. Abhinav Publications. p. 220. ISBN 9788170171935.

- ^ a b Nathalie Comte. "Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World". Ed. Jonathan Dewald. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004. pp 94–108.

- ^ Guenther, Mathias Georg. 'The San Trance Dance: Ritual and Revitalization Among the Farm Bushmen of the Ghanzi District, Republic of Botswana.' Journal, South West Africa Scientific Society, v. 30, 1975–76.

- ^ Raftis, Alkis, The World of Greek Dance Finedawn, Athens (1987) p25.

- ^ Kadman, Gurit (1952). "Yemenite Dances and Their Influence on the New Israeli Folk Dances". Journal of the International Folk Music Council. 4: 27–30. doi:10.2307/835838. JSTOR 835838.

- ^ "Basin with design of dancers". National Museum of China. Archived from the original on 2017-08-11. Retrieved 2017-05-23. Pottery from the Majiayao culture (3100 BC to 2700 BC)

- ^ Kʻo-fen, Wang (1985). The history of Chinese dance. Foreign Languages Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8351-1186-7. OCLC 977028549.

- ^ Li, Zehou; Samei, Maija Bell (2010). The Chinese aesthetic tradition. University of Hawaiʻi Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8248-3307-7. OCLC 960030161.

- ^ Sturgeon, Donald. "Lü Shi Chun Qiu". Chinese Text Project Dictionary (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2022-07-05. Retrieved 2017-05-23.

Original text: 昔葛天氏之樂,三人操牛尾,投足以歌八闋

- ^ Schafer, Edward H. (June 1951). "Ritual Exposure in Ancient China". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 14 (1/2): 130–184. doi:10.2307/2718298. ISSN 0073-0548. JSTOR 2718298.

- ^ "Dance | Ministry of Culture, Government of India". www.indiaculture.gov.in. Archived from the original on 2024-07-30. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ "The Relationship Between Dance And Music || Dotted Music". Archived from the original on 2021-10-27. Retrieved 2021-10-27.

- ^ a b Shawn, Ted, Dance We Must, 1946, Dennis Dobson Ltd., London, p. 50

- ^ Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing, Ballroom Dancing, Teach Yourself Books, Hodder and Stoughton, 1977, p. 38

- ^ a b Lincoln Kirstein, Dance, Dance Horizons Incorporated, New York, 1969, p. 4

- ^ Shawn, Ted, Dance We Must, 1946, Dennis Dobson Ltd., London, p. 49

- ^ Matthew 11:17

- ^ Lincoln Kirstein, Dance, Dance Horizons Incorporated, New York, 1969, p. 108

- ^ Lincoln Kirstein, Dance, Dance Horizons Incorporated, New York, 1969, p. 157

- ^ Scholes, Percy A. (1977). "Dance". The Oxford Companion to Music (10 ed.). Oxford University Press.

- ^ Shawn, Ted, Dance We Must, 1946, Dennis Dobson Ltd., London, p. 54

- ^ Shawn, Ted, Dance We Must, 1946, Dennis Dobson Ltd., London, pp. 50–51

- ^ Moller, Helen and Dunham, Curtis, Dancing with Helen Moller, 1918, John Lane (New York and London), p. 74

- ^ Moller, Helen; Jacobs, Max; Orchestral Society of New York (March 20, 1918). Helen Moller and Her Pupils. Carnegie Hall Archives. Archived from the original on August 22, 2024. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

Complete program collections.carnegiehall.org/C.aspx?VP3=pdfviewer&rid=2RRM1TZL9KAZ collections.carnegiehall.org/a2c80a53-b8fa-4327-b8cf-bbde0cc95651

- ^ *"Helen Moller and Dancers Appear". The New York Times. 27 December 1918. Archived from the original on 22 August 2024. Retrieved 19 July 2024. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1918/12/27/97056760.html

- ^ Moller, Helen; Dunham, Curtis (1918). Dancing with Helen Moller; her own statement of her philosophy and practice and teaching formed upon the classic Greek model, and adapted to meet the aesthetic and hygienic needs of to-day, with forty-three full page art plates;. New York and London: John Lane Company. Retrieved 19 July 2024 – via archive.org.

- ^ "Helen Moller". Musical Courier. No. V79. New York: Musical Courier Company. 1919. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Laban, Rudolf, The Mastery of Movement, MacDonald and Evans, London, 1960, p. 2

- ^ Minden, Eliza Gaynor, The Ballet Companion: A Dancer's Guide Archived 2023-04-08 at the Wayback Machine, Simon and Schuster, 2007, p. 92

- ^ Thoinot Arbeau, Orchesography, trans. by Mary Stewart Evans, with notes by Julia Sutton, New York: Dover, 1967

- ^ Laban, Rudolf, The Mastery of Movement, MacDonald and Evans, London, 1960, pp. 2, 4 et passim

- ^ Laban, Rudolf, The Mastery of Movement, MacDonald and Evans, London, 1960, p. 86

- ^ Abigail Wagner, A Different Type of Rhythm Archived 2016-10-08 at the Wayback Machine, Lawrence University, Wisconsin

- ^ "Kabuki « MIT Global Shakespeares". 8 March 2011. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ Ortolani, Benito (1995). The Japanese theatre: from shamanistic ritual to contemporary pluralism. Princeton University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-691-04333-3.

- ^ Ayansu, E.S. and Whitfield, P. (eds.), The Rhythms Of Life, Marshall Editions, 1982, p. 161

- ^ a b Kariamu Welsh; Elizabeth A. Hanley; Jacques D'Amboise (1 January 2010). African Dance. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60413-477-3.

- ^ a b c Hanna, Judith Lynne (1973). "African Dance: the continuity of change". Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council. 5: 165–174. doi:10.2307/767501. JSTOR 767501.

- ^ Utley, Ian. (2009). Culture smart! Ghana customs & culture. Kuperard. OCLC 978296042.

- ^ Exoticindiaart.com Archived 2006-05-14 at the Wayback Machine, Dance: The Living Spirit of Indian Arts, by Prof. P.C. Jain and Dr. Daljeet.

- ^ Lankalibrary.com Archived 2007-03-09 at the Wayback Machine, "The yakun natima — devil dance ritual of Sri Lanka"

- ^ "The Indonesian Folk Dances". Indonesia Tourism. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ a b Badley, Bill and Zein al Jundi. "Europe Meets Asia". 2000. In Broughton, Simon and Ellingham, Mark with McConnachie, James and Duane, Orla (Ed.), World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East, pp. 391–395. Rough Guides Ltd, Penguin Books.

- ^ Recep Albayrak Hacaloğlu. Azeri Türkçesi dil kilavuzu. Hacaloğlu, 1992; p. 272.

- ^ Subhi Anwar Rashid, Mesopotamien, Abb 137

- ^ Carol Lee (2002). Ballet in Western Culture: A History of Its Origins and Evolution. Psychology Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-415-94257-7.

- ^ Kourlas, Gia (2016-09-02). "Hiplet: An Implausible Hybrid Plants Itself on Pointe". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-01-01. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- ^ a b John Charles Chasteen (1 January 2004). National Rhythms, African Roots: The Deep History of Latin American Popular Dance. UNM Press. pp. 8–14. ISBN 978-0-8263-2941-7.

- ^ Margaret Musmon; Elizabeth A. Hanley; Jacques D'Amboise (2010). Latin and Caribbean Dance. Infobase Publishing. pp. 20–23. ISBN 978-1-60413-481-0.

- ^ a b Celeste Fraser Delgado; José Esteban Muñoz (1997). Everynight Life: Culture and Dance in Latin/o America. Duke University Press. pp. 9–41. ISBN 978-0-8223-1919-1.

- ^ "Dance/Movement Therapy's Influence on Adolescents Mathematics, Social-Emotional and Dance Skills | ArtsEdSearch". www.artsedsearch.org. 16 April 2019. Archived from the original on 2020-04-02. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- ^ "NDEO > About > Dance Education > Dance Studios". www.ndeo.org. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ "NDEO > About > Dance Education > PreK-12 Schools". www.ndeo.org. Archived from the original on 2024-09-10. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ Sagolla, Lisa (April 24, 2008). "(untitled)". International Bibliography of Theatre & Dance. 15 (17): 1. Archived from the original on January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "Dance Teacher | Berklee". www.berklee.edu. Archived from the original on 2022-10-04. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ^ Risner, Doug (December 2000). "Making Dance, Making Sense: Epistemology and choreography". Research in Dance Education. 1 (2): 155–172. doi:10.1080/713694259. ISSN 1464-7893. S2CID 143435623.

- ^ "dance - Choreography | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2022-10-04. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ^ a b Schupp, Karen (2019-04-03). "Dance Competition Culture and Commercial Dance: Intertwined Aesthetics, Values, and Practices". Journal of Dance Education. 19 (2): 58–67. doi:10.1080/15290824.2018.1437622. ISSN 1529-0824. S2CID 150019666.

- ^ Wilcox, Emily (22 December 2017). "Performing Bandung: China's dance diplomacy with India, Indonesia, and Burma, 1953–1962". Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 18 (4): 518–539. doi:10.1080/14649373.2017.1391455. S2CID 111380513. Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey A. (2013-09-30). "Preventing dance injuries: current perspectives". Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine. 4: 199–210. doi:10.2147/OAJSM.S36529. ISSN 1179-1543. PMC 3871955. PMID 24379726.

- ^ Li, Fengfeng; Adrien, Ntwali; He, Yuhuan (2022-04-18). "Biomechanical Risks Associated with Foot and Ankle Injuries in Ballet Dancers: A Systematic Review". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19 (8): 4916. doi:10.3390/ijerph19084916. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 9029463. PMID 35457783.

- ^ Center, Smithsonian Lemelson (2020-05-28). "A Better Pointe Shoe Is Sorely Needed". Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. Archived from the original on 2022-12-13. Retrieved 2022-12-13.

- ^ Abraham, Suzanne (1996). "Eating and Weight Controlling Behaviours of Young Ballet Dancers". Psychopathology. 29 (4): 218–222. doi:10.1159/000284996. ISSN 1423-033X. PMID 8865352. Archived from the original on 2014-08-29. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ^ Walton, Courtney C.; Osborne, Margaret S.; Gilbert, Paul; Kirby, James (2022-03-04). "Nurturing self-compassionate performers". Australian Psychologist. 57 (2): 77–85. doi:10.1080/00050067.2022.2033952. ISSN 0005-0067. S2CID 247163600. Archived from the original on 2022-12-03. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ^ Doria, Nicole (January 12, 2022). "Dancing in a culture of disordered eating: A feminist poststructural analysis of body and body image among young girls in the world of dance". PLOS ONE. 17 (1): e0247651. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1747651D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0247651. PMC 8754298. PMID 35020720.

- ^ Arcelus, Jon; Witcomb, Gemma L.; Mitchell, Alex (2013-11-26). "Prevalence of Eating Disorders amongst Dancers: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis". European Eating Disorders Review. 22 (2): 92–101. doi:10.1002/erv.2271. ISSN 1072-4133. PMID 24277724.

- ^ TikTok cultures in the United States. Trevor Boffone. Abingdon, Oxon. 2022. ISBN 978-1-000-60215-9. OCLC 1295618580.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Warburton, Edward C. (2022-07-01). "TikTok challenge: dance education futures in the creator economy". Arts Education Policy Review. 125 (4): 430–440. doi:10.1080/10632913.2022.2095068. ISSN 1063-2913. S2CID 250233625. Archived from the original on 2022-12-03. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ^ "VILLA OF THE MYSTERIES". Pompeii sites. Archived from the original on 31 January 2024. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

Further reading

- Abra, Allison. "Going to the palais: a social and cultural history of dancing and dance halls in Britain, 1918–1960." Contemporary British History (Sep 2016) 30#3 pp. 432–433.

- Blogg, Martin. Dance and the Christian Faith: A Form of Knowing, The Lutterworth Press (2011), ISBN 978-0-7188-9249-4

- Carter, A. (1998) The Routledge Dance Studies Reader. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16447-8.

- Cohen, S, J. (1992) Dance As a Theatre Art: Source Readings in Dance History from 1581 to the Present. Princeton Book Co. ISBN 0-87127-173-7.

- Daly, A. (2002) Critical Gestures: Writings on Dance and Culture. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6566-0.

- Miller, James, L. (1986) Measures of Wisdom: The Cosmic Dance in Classical and Christian Antiquity, University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-2553-6.

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Historic illustrations of dancing from 3300 BC to 1911 AD from Project Gutenberg

![A satyr dancing. A fresco from the cubiculum in the Villa of the Mysteries. From Pompeii. Date: 80 to 70 BCE [70]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d5/Fresco_Villa_dei_Misteri_28.JPG/182px-Fresco_Villa_dei_Misteri_28.JPG)